On March 17, you’ll probably be bombarded by people wearing their finest “Kiss Me I’m Irish” or emerald-green attire to celebrate a man called Saint Patrick. We tend to mark the occasion with parades, corned beef and cabbage dinners, and shamrock-wearing festivals around the country.

But did you know that the patron saint of Ireland wasn’t even Irish? Or that his given name was Maewyn Succat? You can read more fascinating facts about him on the History.com site.

And while we may equate Irish American Heritage Month to St. Patrick, Irish Americans have made other, more fascinating and significant contributions to our society and culture than honoring this one man. As a result, in 1995, Congress first proclaimed March as Irish American Heritage Month. Today, the U.S. president issues a proclamation to commemorate the occasion each year.

Ireland’s Great Potato Famine Changes America

Scots-Irish, or Scotch-Irish, were the early transatlantic Irish immigrants to America in the early 17th century, according to the New York Public Library. “A majority of Scotch-Irish settled throughout the Appalachian states of Virginia south to Georgia.”

Then in 1845, a white fungus began to appear on Irish potato crops, prompting “one of the first mass migrations to the United States by a single ethnicity.” Before then, most Irish immigrants in America were members of the Protestant middle class, but during the three years of the potato famine, “Close to 1 million poor and uneducated Irish Catholics began pouring into America to escape starvation.”

Due to their “alien religious beliefs and unfamiliar accents to the American Protestant majority,” many of the new Irish immigrants had trouble finding work and being accepted.

So they brought a piece of home to America: Originally a religious holiday in Ireland, St. Patrick's Day in the States has “evolved into a celebration for all things Irish.”

The first Irish parade on March 17, 1762, in New York City honored St. Patrick’s death on March 17, 461 A.D. It was a showing of their homeland pride—and an introduction to politics.

That parade featured Irish soldiers serving in the English military. It sparked Irish Americans’ realization of their political power and they began to organize the first unions. Mary Harris (also known as Mother Jones) “committed more than 50 years of her life to unionizing workers in various occupations throughout the country.”

St. Patrick’s Day parades, like the one President Harry S. Truman attended in New York City in 1948, have become events for the many “Irish Americans whose ancestors fought stereotypes and racial prejudice to find acceptance.” Locally for years, Dublin, Calif., has become the Bay Area hometown for those celebrating their Irish American Heritage in March.

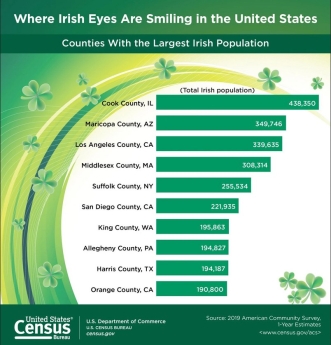

Who is Irish American according to this graphic from the 2019 U.S. Census.

- 30.4 million or 9.2%: The number/percentage of U.S. residents who claimed Irish ancestry in 2019.

- 111,886: The number of foreign-born U.S. residents who reported Ireland as their birthplace in 2019.

- 438,350: The number of people living in Cook County, Ill., who claimed Irish ancestry in 2019, the largest of any county in the nation.

Irish Americans in the Bay Area

When the Irish emigrated to the United States, many came to the San Francisco Bay Area around the time of the Gold Rush.

“Irish immigrants made up the majority of San Francisco's working class, constituting 13 percent of San Francisco's total population and more than 21 percent of the labor force in 1870. By 1880, approximately one-third of the city's population was of Irish descent.

“Sam Brannan is believed to be the first person to become a millionaire in the wake of the Gold Rush,” FoundSF.org also offers. “By the mid-1850s, Brannan owned about 20 percent of the land in San Francisco.”

Eventually, the Irish immigrant community became influential in city politics. How? According to Found SF, “They were native English speakers, understood the U.S. political system and because of their sheer numbers. In 1867, San Francisco's mayor was an Irish Catholic: Frank McCoppin. Irish political mobility was also aided by the fact that unlike the East Coast, California had much less entrenched bigotry against the Irish.” But we need to be honest: It is cited on FoundSF’s website and Irish America that the Irish Catholics were also among the groups who wished to keep Chinese laborers out of the state.

Regardless of being Anglo-Protestant or Irish Catholic, Americans with Irish heritage continue to reach high levels of government, as demonstrated by the successes of many mayors, senators, governors and presidents—including Presidents John F. Kennedy, Ronald Reagan and Joseph Biden.

Irish Americans also have played key roles in Los Angeles: Edward Doheny became one of the region’s wealthiest oil tycoons (and inspired There Will Be Blood); William Mulholland once worked for the city’s water company and developed the Los Angeles Aqueduct (and inspired Chinatown).

Irish American notables and celebrities who have portraits in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., include F. Scott Fitzgerald, Grace Kelly, Nolan Ryan and Muhammad Ali. First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy has Irish heritage on her mother’s side of the family. Other famous Irish American women, who don’t have their portrait in the Smithsonian museum but maybe should, include actress Maureen O’Hara, artist Georgia O’Keeffe, singer Ella Fitzgerald, philanthropist “The Unsinkable Molly Brown” and cook “Typhoid Mary” Mallon.

The list goes on and on when you think of the contributions that Irish Americans have had on our culture, history and society. Their heritage deserves to be recognized and celebrated, and it is no wonder that we all want to have the “Luck of the Irish”—and not only for one month of the year.