Every spring, The American Cultures (AC) Center at UC Berkeley selects two recipients for the AC Excellence in Teaching Award. This award recognizes “individual faculty’s exemplary teaching in the American Cultures curriculum” and for their “inspiring and sustained commitment to creating a learning space able to hold the multiple challenges and opportunities that teaching AC content requires.”

In 2020, our Dr. Seth Lunine, who teaches Geography 50AC: California, was honored in a virtual award ceremony.

Why Dr. Lunine

In short, Seth was selected for the AC Excellence in Teaching Award because his courses “enable students to participate in spaces of visibility, vulnerability and connection that mirror and mold critical thinking and other scholarly engagement within the AC curriculum.”

In fall 2020, all 48 spots were filled for his FPF course, which explores California and its distinctive traits. His students discussed the good—its dynamism, natural wealth and diversity of peoples—and the bad—exploitation and racial inequalities.

He incorporates Bay Area community partners in his course through his participation in the American Cultures Engaged Scholarship (ACES) Program and Creative Discovery Fellows Program. According to the American Cultures Center, Lunine’s “students design and produce ‘deliverables’ that embody not only original research and substantive analysis but also meaningful interventions in real-world social and economic justice issues.”

Let’s find out a little more about this amazing professor.

What is your educational and professional background?

I received both my B.A. and Ph.D. in geography from UC Berkeley, where I’m currently a lecturer, in addition to teaching at FPF. My professional background includes working as the program director for a private foundation that provides grants to community-based nonprofit organizations throughout the U.S. My focus at the foundation included affordable housing, education and mentorship, and economic development in central cities and Native American nations.

Why teach geography as a subject area in American Cultures? And do you always focus on California?

My interests in spatial histories of cities, cultures and economies in California necessarily engage with American Cultures curriculum, which centers on theoretical and analytical issues relevant to understanding race, culture and ethnicity in American history and society. California has, of course, long been home to significant multiracial and global populations. California is a compelling place to study overlapping and interacting African American, Asian American, European American, Latinx and Native Californian groups, while constantly considering the formation and novelty of these categories themselves.

In addition to Geography 50AC: California, I’ve taught classes about the San Francisco Bay Area, including:

-

Geography 72AC: The Bay Area

-

Geography 170: Bay Region Landscape

-

Geography 70AC: The Urban Experience: Race, Class and the American City

-

Geography 181: Urban Field Studies

When did you begin teaching for the Fall Program for Freshmen?

Unfortunately, I was unaware of the Fall Program for Freshmen before Spring 2015—“unfortunately” because I certainly would have benefitted from FPF when I was an overwhelmed first-semester undergrad at UC Berkeley.

I learned of FPF serendipitously, when a student assistant at FPF requested my syllabus for Geography 50AC: California, which I continue to teach. I soon learned that FPF sought to expand course offerings about California at a new FPF campus in San Francisco. I taught in San Francisco for three years; field trips, tours and the academic equivalent of scavenger hunts helped the classes take advantage of our location in “the city.”

Could you describe a typical class day of learning in Geography 50AC last fall?

With remote learning, classes typically comprised a lecture interspersed with individual writing exercises so students could share their ideas and insights—as well as their questions and concerns—about course topics and assigned readings.

I also introduced periodic small-group activities designed to help students synthesize course materials and understand how their own experience and knowledge shape their perceptions of California and its people, as well as of themselves and each other. Pairs of students facilitated a weekly discussion section—primarily through developing questions and activities—and then leading conversations about assigned readings.

What was the impact of the Live Online format on your classroom?

Synchronous remote learning certainly changed the dynamics of the “classroom.” My initial challenges revolved around gauging students’ comprehension of, and engagement with, course material during lectures.

At the same time, remote learning spurred teamwork. Students quickly adapted, focused on solutions, remained engaged, and treated themselves and each other with patience, if not kindness. We collectively devised several advantageous uses of Zoom, such as individual meetings to work on course projects and asynchronous course activities.

What is the ACES project and how do you incorporate this into your course?

American Cultures Engaged Scholarship (ACES) provides unique opportunities for students to participate in experiential learning and actively address social justice issues through collaborations with community partners.

FPF students in Geography 50AC: California have partnered with the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project and the Tenderloin Neighborhood Development Corporation. In fall 2019, several groups addressed housing insecurity, particularly among UC Berkeley students, including Berkeley NEED, and UC Berkeley’s Basic Needs Center, Student Advocate’s Office and Student Legal Services.

These partnerships enabled students to extend, contextualize and creatively apply course concepts related to gentrification, racialized displacement, housing activism and “the right to the city.” Students designed and produced deliverables, such as a resource guide for low-income Tenderloin residents; story art for the Basic Needs Center; a short film on People’s Park development debates; infographics on tenants rights; and Tenderloin community organizing posters written in Cantonese, English and Spanish.

In fall 2020, Chancellor’s Public Fellow and Geography Ph.D. candidate Kerby Lynch introduced students to an array of issues related to abolition politics and activism in the midst of the global pandemic, the economic downturn, the rise of fascism and ongoing urban rebellions. In all, students learned about the concepts and values structuring abolitionist politics and how these values related to our coursework.

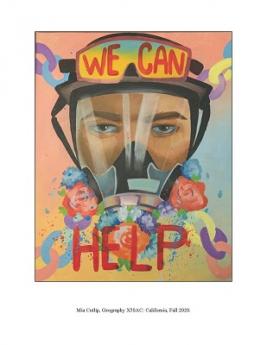

The students considered pragmatic applications of abolition politics to an array of contemporary issues, such as police violence, transformative justice, immigrant rights, mass incarceration, sinophobia, affirmative action and more. They then addressed these issues by designing and producing public-facing projects, such as digitized augmented-reality galleries, experimental art work, social justice events for the campus community and policy position papers.

ACES work at FPF has created opportunities for student engagement, interaction and learning that are impossible to replicate in the classroom. Perhaps most significant was the generative interaction between students and community partners. For example, during weekly meetings with affordable housing residents in the Tenderloin or during community-planning sessions in People’s Park, we found few templates or models for our ACES work.

Instead, our collaborations meant experimentation and collective learning. In this sense, collaborative research with community partners has been inherently innovative, comprising face-to-face interaction, problem-solving and learning-by-doing. This has required active listening, engendered reciprocal trust and helped students unfamiliar with the work of community partners move from initial interest to active empathy. Many students were all too familiar with issues addressed by our partners.

Yet our ACES work created opportunities for these students to recognize the significance and power of their own experiential knowledge. ACES projects have proven to be the most meaningful and consequential elements of my FPF classes for both myself and the students during our time together.

What draws you to teaching at FPF?

I cannot overstate the significance of FPF students’ intellectual curiosity, which engenders engagement with not only course materials, but also with each other—especially in small FPF classes.

I truly value the diversity of FPF students, as well.

I’ve had students from many California cities and suburbs, as well as from the Central Valley and Sierra foothills. From Baltimore, Boston, Chicago and New York City. From Arizona, Florida, Maine and Minnesota. From China, India, Mexico, Thailand and more. I always admire international students’ energy and effort at FPF.

The mix of students’ experiences, racial and ethnic identities, political inclinations, gender identifications, religious affiliations, intended majors and anticipated careers animate course concepts and themes. This diversity of backgrounds and perspectives certainly enhances my teaching, too.

Perhaps most significant is FPF students’ serious optimism and search for solutions—last fall more than ever. Their efforts, interests and integrity inspire me.

So that leads us to one final question: What do you hope your students will do with what they have learned in your course?

My loftiest teaching goal is to create a community of stakeholders among diverse students, regardless of their backgrounds and intended majors. I hope to instill in each student an enduring understanding and a pragmatic interest in the intertwined issues of social and economic injustice that help structure Geography 50AC: California. This may directly influence students’ subsequent coursework and academic interests, but may also inform politics and political participation.

Moreover, I hope that all students—especially first-generation college students from groups that are underrepresented at UC Berkeley—will find their voice and footing at UC Berkeley, and come to understand that they do not just belong at UC Berkeley, but are the university’s greatest asset.