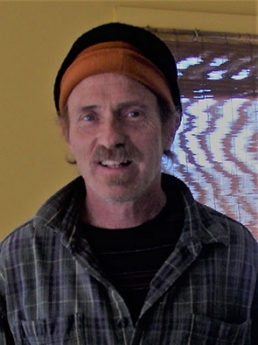

“He is such a naturally talented teacher that I bet a knitting class with him would be fun and informative,” a Post-Baccalaureate Certificate Program in Writing student wrote in one of Daniel Coshnear’s end-of-course evaluations. This type of praise is just one of the many reasons why Coshnear is among this year’s honored instructors—his dedication to fulfilling our educational mission and encouraging learning beyond classroom walls are others.

Coshnear, who has taught fiction writing in the Bay Area since 1997, began teaching for us in 2000. His writing and editing experience, along with an unending supportive attitude for his students’ creative writing, has made him a favorite instructor in the Writing certificate program. Yet, Coshnear doesn’t believe that he “teaches” writing. So if he doesn’t “teach,” what makes his course such a rewarding experience?

1. Learning doesn’t stop once the class is over.

Coshnear is both a student and an instructor—and his own educational experiences continue to influence how he conducts his classes.

- As the student: Years ago, Coshnear earned his M.F.A. from San Francisco State University. He also has taken his own student experiences from various writing workshops in New York City to create a classroom environment that helps his students thrive.

- As the instructor: “There is so much to learn regarding teaching to write, and how do you really know that you learned anything? There are glimpses, but—I think somewhat consciously, at first, and later less so—you begin to settle into a style that feels comfortable. I like posing problems for discussion, and discussions go better for me if I haven’t thought through all the facets, haven’t come to any firm conclusions. Just as so much writing is reading, I think much of teaching is learning—‘To be there and ready,’ as Toni Cade Bambara put it.”

2. He’s ready, and present.

Coshnear’s eager students make it easy for him to be in the present while teaching. In turn, their enthusiasm helps him understand their expectations of the class from the beginning. With their goals in mind, Coshnear is able to make them feel comfortable in their writing regardless of their background or initial ability.

“He is well organized, cares about his students, is very supportive of our writing efforts and very smart in his teaching,” is how one student in Coshnear’s courses describes him. Another commends him thus: “I got the feeling that because of him the group really came together. In addition to Dan’s well-prepared and highly instructive lectures, we were able to learn from each other.”

3. Success is personal.

Coshnear’s vision is that each student discover his or her writing voice by the end of the course, that his students know they’re on the right path. That is what Coshnear considers success. He is also not shy about presenting the reality of a writing career upfront. It is not traditional thinking, and his students seem to appreciate that.

“Success means to have continued to write now 12 years after completing a graduate program in writing,” wrote Coshnear in a 2014 piece for The Los Angeles Review, “to still find pleasure in it, to publish occasionally, to still, now and then, surprise myself. Success means sustaining hard work in a pleasurable way.”

4. Engagement is important for both instructor and student, writer and reader.

Remember Coshnear’s own M.F.A. professors and teachers? He credits them with instilling writing habits that keep him moving forward. He strives to pass along those same insights by keeping his students engaged.

“I have felt very drawn to teachers who seemed genuinely excited about the material they taught,” Coshnear explains. “Very good stories and poems and essays yield new discoveries even after you’ve read them 10 times. I often get new insights from hearing what students think. My favorite teachers modeled attitudes, habits of thought, openness.

“As a teacher and as a student of writing,” Coshnear continues, “you read a lot of stories, you notice patterns, what tends to work, and what tends to put the reader in a doubtful or contentious mood. There are no absolutes. Every time I’m tempted to say always or never, I think of a case that breaks the rule—and brilliantly.”

5. Writers need to take an opportunity where they can find it.

Coshnear is a mainstay in our post-baccalaureate writing certificate. Liz McDonough, the writing certificate’s program director, says, “Whether he is laying the foundation of important writing skills or helping cement student commitment to the completion of our program, he understands the program’s goal.”

It is not surprising then that Coshnear was asked to be a staff adviser on Ursa Minor, the Post-Baccalaureate Certificate Program in Writing’s student-produced literary journal. The program provides a chance for writers (and editors) to test the waters and navigate the publication process as part of their certificate education.

“It’s hard for any of us to get our work out in the world,” says Coshnear on the importance of the student journal. “It’s easy to get discouraged. I’m very glad that Ursa Minor has come into being. Because we have a relatively low number of submitters, it’s an opportunity for Extension students to have their work read carefully and to receive a somewhat more detailed critical response than what you would get from most literary magazines. For a handful of students each year, it’s a chance to see their work in print, and to better understand the process that leads to that ‘product’ we all love so much. In class, we all say that it is important to draw the reader in with the first sentence, to hook her or him with the first paragraph. We say it, but I think Ursa Minor editors really understand it. The experience of reading a stack of anonymous submissions is great for any writer who intends to send out work.”

6. The best feedback is a student writing something true to self.

“The best feedback I receive as an instructor is intangible,” Coshnear points out. “Someone who begins the semester writing in a writerly style, a little stilted, a voice that seems not his or her own and perhaps midway through or later, she or he explores some nuance of experience, risks being misunderstood, writes something true and memorable. That’s very cool. Maybe it is vain of me to call that feedback; it is evidence that the class is working, that something has been discovered. I’ve had a number of classes spawn writing groups, some of which I know are still thriving. What could be better than that?”

Potential students who are shy about their writing skills but who have some great ideas in their heads need not worry in Coshnear’s courses. He encourages everyone to get those ideas on paper, to seek out other shy people, to find others who want to write.

His advice: “Share. It is very, very, very rare in my experience—and especially at UC Berkeley Extension—that fellow writers are cruel to one another. I think most who’ve been at it for a while would acknowledge that reading others’ work critically and carefully with an eye for making it better makes them better writers.”

For that critical, careful and constructive advice to his students, we thank him.