Emerging Leaders: Josh Halstead

Editor's note: This article was originally published on AIGA blog Emerge. It has been republished with their permission.

Hi Josh! Can you tell us a little bit about yourself?

Hey there. Most importantly, I’m a brother to two wonderful siblings: Ryan and Paige. They, along with my parents, provide drive and support for anything I do personally and professionally.

I have several things that occupy my day-to-day. First, I’m a senior manager of brand design at a Bay Area fintech called Oportun where I’m responsible for all things brand identity (things like visual brand guidelines, our digital design language, etc.). Second, I’ve been adjunct faculty at UC Berkeley Extension in their art and design department for the past couple years where I teach a course called Visual Design Principles. Third, I would consider myself an avid disability advocate.

My focus in grad school is investigating the entanglement of disability identity, culture, and design.

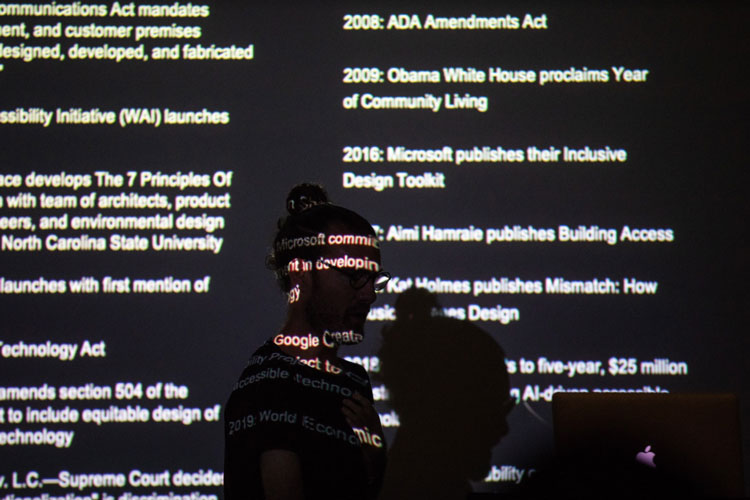

This thread led me to work on my master’s in disability studies at CUNY. My focus in grad school is investigating the entanglement of disability identity, culture, and design. This line of inquiry has given me the opportunity to share my research at venues such as the 2019 AIGA Conference, Stanford University’s inaugural disability studies conference, and Google, among others. To the passive observer, this might seem like a lot, but each area works harmoniously with the others—in a way that informs my commitment and action to all the others.

I would consider myself an avid disability advocate.

How did you enter the design field?

When I was about 10 years old, instead of a lemonade stand, I decided to start a greeting card business. This was a way for me to cultivate my love of art and design while also (perhaps) prototyping a proof-of-concept for myself and my parents that art could be a financially supportive endeavor.

On the coattails of the late ‘90s, I depicted skateboarders in pen and ink and watercolor. Greg, the general manager of skate company, Active (then Active Skateboard Company), let me set up a three-tier card display at the front desk on consignment. This venture lasted a few years. Before exploring the intersection of design and business again in high school, creating art for my first band introduced me to formal design programs and provided a constant outlet for my imagination.

When I was 15, I played the drums for a Led Zeppelin cover band called Midnight Sun.

When I was 15, I played the drums for a Led Zeppelin cover band called Midnight Sun. At the time, my dad was experimenting with Photoshop to create labels for the family company’s boxed nails, and I figured that the first step to the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame was to create merch. So, through trial and error, I created band stickers. Once I saw my fellow classmates attaching our band stickers on their backpacks (and perhaps on their textbooks too—sorry Vineyard Junior High), I was hooked.

My second design-based “business venture” was at 17 when three friends and I started our own T-shirt company called Rype. The company created a framework for me to continuously expand my design know-how while fostering an insatiable creative curiosity. As a result, I applied to the graphic design program at ArtCenter College of Design out of high school and was accepted. After graduation, I worked for a global branding firm, Landor, which fit well with my compulsive desire to merge design and business.

What are some of your favorite projects that you have worked on? What have you learned along the way?

What are some of your favorite projects that you have worked on? What have you learned along the way?

Great question. There are several projects, but I would rather explain one project in particular—Book 37—then zoom out to explain how it’s influenced ongoing projects in design pedagogy and disability advocacy.

Book 37 grew out of my experience commuting to my college internship at AdamsMorioka. Using public transportation, I became aware of the large houseless population in Los Angeles. At the time I was also ardently exploring spirituality, and I found it troubling how many of my so-called peers (i.e., “working professionals”) denied individuals without a home their constitutive humanness through microaggressions like showing fear. I noticed that fear policed social politics in a way that conversation and even eye contact appeared to be taboo between those who traversed Broadway to get to the office and those who called Broadway home.

I found it troubling how many of my so-called peers (i.e., “working professionals”) denied individuals without a home their constitutive humanness through microaggressions like showing fear.

I was a young twentysomething trying to soak up as much knowledge as possible about the world. Sure, I was learning how to set type in neat, three-column grids for newsprint. But what does it mean for that same newsprint to be a blanket—an observable use we never discussed in class? Further, whose perspectives were included in the columns of The Los Angeles Times and whose were left out? And what did that mean for the collective politics of knowledge—particularly how I was going about structuring my own empirical knowledge outside of academics? These questions followed a series of reckonings where I reflected on how little I knew about houselessness and systemic oppression.

Book 37, therefore, was a self-published book of quotes I gathered from eight months of fieldwork in Los Angeles, Pasadena, Venice, and Fontana, California, where I asked people from the houseless community to share their perspectives on life.

This project shaped my understanding of design because I had no choice but to extend my definition of design to the social.

This project shaped my understanding of design because I had no choice but to extend my definition of design to the social. It situated me in a position to grapple with my multiple identities—white, cis, male, middle-class, heterosexual, disabled—and how these identities were not static but fluidly codesigned through internal reflection and social interactions. Ergo, there was no way to hide my identities as a researcher in a one-on-one interview.

If I wanted to truly learn, I had to understand how my identities influenced my perception of conversations I had with individuals claiming myriad identities.

Despite my hesitation, I was delighted with how I was welcomed into the houseless community. More times than not, when I approached someone for a conversation, I would be ushered into a one-hour window into their life story, given introductions to partners and friends, and received the occasional spontaneous hug. I was taken with how freely affection was expressed in this community and how starkly it misaligned with the community I shared train space with on the 6 am Metrolink.

Cindy told me about her previous career at Disney; Darnell explained how his nightly ritual involved removing sharp glass from the grassy play area of the neighborhood park, because parents would allow their children to run around without shoes; Lucy told me about subcommunities formed to support one another’s health, shelter, and sense of belonging.

Though I documented several conversations and published quotes that I hoped would change untested assumptions about houselessness and the houseless community, what I considered the true success of the project was being able to walk down Colorado Boulevard and greet new friends by name.

That summer, I transitioned from paper to people, and the projects I prioritize now reflect that value. Oportun, where I manage brand design, builds inclusive products for individuals who may (or may not) have a credit history. Berkeley Extension allows me to teach high-level design to a broader population than typically observed in our American arts institutions.

Berkeley Extension allows me to teach high-level design to a broader population than typically observed in our American arts institutions.

Disability studies and advocacy build on my lived experience as a disabled person and gives me the opportunity to highlight underrepresented narratives and challenge unchallenged taboos. Book 37 shook my narrow focus on the materiality of design and challenged me to engage its cultural, social, and political consequences and opportunities. I count myself fortunate to have had this experience early on, because it’s allowed me to unapologetically create a career that will hopefully be as beneficial to others as it is to myself.

Disability studies and advocacy build on my lived experience as a disabled person and gives me the opportunity to highlight underrepresented narratives and challenge unchallenged taboos.

You are a masterful speaker and teacher. Can you share tips for anyone who may be interested in going down that path?

Thank you. “Masterful” is a flattering word, and if my speaking and teaching come off this way, it’s not without hours of self-doubt, rewriting, and preparation.

My pathway to speaking and teaching was simply having a point of view. I always have a point of reference in my own life that drives me into newfound arenas. For example, I became more interested in teaching after mentoring a couple of young designers who had just graduated but had little to show for it in their portfolios. They had just spent close to $100,000 in tuition and would be overlooked by the agencies they wished to work for because they didn’t have examples of brand systems, digital applications, and space-based graphic design. Further, I had a colleague at the time who had a visceral disdain for grids—yet her work was always the front-runner for client presentations.

Having ingested modernist ideals at ArtCenter, I first thought this was sacrilege before I started to practice her artful take on graphic design myself. In my interview for the teaching position, I shared how these examples shaped my own work and would continue shaping my pedagogy—if given the chance.

UC Berkeley Extension gave me that chance, and my required textbook is Helen Armstrong’s Graphic Design Theory—ensuring students receive early exposure to a more diverse theoretical framework of graphic design.

I started talking openly about disability design a couple years ago. This was initially prompted by a colleague in London who asked me to present my thoughts on how our design field was responding to the growing visibility of access needs in products and technology. After beginning research, I noticed that what I knew disability to be from my own lived experience was not well represented in case studies on design blogs.

This bifurcation of disability and creativity made little sense to me; I am a designer because of my disability, not in spite of it.

Disability was (and still is) often portrayed as a tragedy with disabled people as the “grateful” beneficiaries of charitable design projects. This bifurcation of disability and creativity made little sense to me; I am a designer because of my disability, not in spite of it. My brain is probably better suited for something like accounting, but it’s the day in, day out hacking and problem-solving I do in a broadly inaccessible world that gives me a knack for creating new things.

My first presentation was cathartic and introduced many of my colleagues to a less popular narrative of disability being inherently creative. I was given the opportunity to present my thoughts to Landor’s London, New York, Cincinnati, and San Francisco offices.

I noticed that what I knew disability to be from my own lived experience was not well represented in case studies on design blogs.

I give prominence to lived experience, because we (myself included) often devalue how much our experiences have to offer. We are quick to bestow expertise on others and illegitimacy on ourselves, and this feeling of being an imposter has the potential of being the single most fortified barrier between us and our aspirations.

I did not know how to be a “good” teacher before given the opportunity; I did not know how to be a cogent speaker before being asked to unfurl my life story on a global stage. And that made me realize that no one knows how to do it before actually doing it.

If we foreground lived experience, it will challenge us to push beyond textbooks and engage diverse perspectives in perpetuity. Understanding that the script of your life is an autobiography (not biography) is liberating because you can challenge prescripted narratives—whether they come from the inside or outside.

If we foreground lived experience, it will challenge us to push beyond textbooks and engage diverse perspectives in perpetuity.

You are clearly a continuous learner. Why is it so important to stay curious and dedicated to the art of learning? What are you currently focused on as 1. a student and 2. a teacher?

My working framework for knowledge is that I don’t yet know what I ought to know. For example, if I stand in line and buy a chocolate croissant from Starbucks, that event can be told from myriad perspectives. I could tell you autobiographically. The cashier could tell you from his perspective. The person behind me could narrate the event, highlighting my anticipatory dancing in place, and the person in front of me might describe the event through their discernment of audible and haptic feedback they received from my tapping feet.

An experienced designer might tell the story with the intention of underscoring a favorable or intolerable customer experience, and the historian passerby might illumine how my standing in line reflects American militarism and asymmetries of authority and power. Point being, the recognition that knowledge is co-produced and negotiated can prompt us into an ever-expansive world of knowledge-making from unexpected angles.

I’m focused on building a disability design framework that fosters belonging.

As a student, I’m focused on building a disability design framework that fosters belonging. Applying a disability justice framework and Aimi Hamraie’s call for a new field of critical access studies, I’m interested in how physical, social, and virtual space can be used to ask questions (rather than supply answers) about disability.

For example, a current passion project called Artistry of Access gathers a team of disabled folks from the U.S. and Canada. Together, we are developing an open-sourced design methodology grounded in creative workarounds we practice every day—from getting dressed to navigating public transit.

With respect to teaching, I’m now working on my first online course. Visual Design Principles is now part of our UX design certificate program and will be offered to a broader population of students in the U.S. and abroad. Developing and redeveloping my course content has been an opportunity to be mindful of the principles of universal design in education—making content perceptible and resonant in diverse modalities and cultures.

Can you tell us about a mentee or student of yours who’s left an impression on you? — How about a mentor or teacher who’s left an impression on you?

Honestly, there is no possible way for me to cherry-pick a single example of how a particular student or mentee has impacted me. Each person I have the opportunity to build a relationship with is of equal and unquantifiable value. My students’ thoughtful and collective feedback has helped me become a better educator. Kimberly Elam echoes this point in her introduction to Grid Systems: Principles of Organizing Type: “This book, and others in the series, is indebted to my students. … Design education is a fluid process that constantly evolves.”

Likewise, my evolution in my personal and professional life is indebted partly to my students. And there is nothing like receiving an unexpected email in the middle of a workday expressing excitement about an assignment or being thanked for last week’s lesson.

My students’ thoughtful and collective feedback has helped me become a better educator.

The other piece of that equation, however, is of course my mentors. Again, I couldn’t possibly cherry-pick—as individuals like Trevor Wade, Anthony Light, and Chris Lehmann took it upon themselves to show me the ropes of the design industry. Through dialogue and attentive observation, they modeled (and continue to model) how professionalism and friendship don’t have to be mutually exclusive categories.

In education, I always return to the lessons I learned in Professor Leah Hoffmitz’s Type 1 and Errol Gerson’s Entrepreneurship 101. Leah showed me that 99% of my effort wasn’t worth a dime until I gave her the last 1%. Errol (closing in on his 50th year at ArtCenter) taught me I could change the world if I stuck out 1/8 of an inch.

In the disability community, I’m privileged to be mentored by Rosemarie Garland-Thomson and Neil Marcus.

In the disability community, I’m privileged to be mentored by Rosemarie Garland-Thomson and Neil Marcus. Both have moved mountains in the disability studies field and disability rights movement; both also allow me to break bread with them and ask questions until my mind’s content. Likewise, Errol Gerson met me for coffee on several occasions to talk about inflection points in life far beyond curricula.

What I’ve learned from my students and mentors alike is that relationships are relationships. We can label relationships as professional, social, romantic, or familial, but they are propelled through selflessness, mutuality, and trust. I’m indebted to my family, students, and mentors for who I am today and who I hope to be next week.

Before we wrap up, I wanted to ask about your frequent use of Twitter. What are the advantages of digital activism?

I try to be a frequent user of Twitter, but sometimes it’s hard while juggling other commitments. In contrast, I try to be an intentional (but transient) user—sharing thoughts and resources without self-imposed or time-sensitive expectations.

My Twitter account is primarily used for disability advocacy and education because of the growing potential of digital activism.

My Twitter account is primarily used for disability advocacy and education because of the growing potential of digital activism. A 2016 article in Stanford Social Innovation Review titled “Transforming Activism: Digital Era Advocacy Organizations” illustrated how digital activism is interrupting the way in which citizens interface with institutional power. The authors point out that social media platforms like Twitter and Facebook interrupt how society can organize similar to how Uber, Airbnb, and Google interrupted the taxi, hospitality, and content creation industries, respectively.

From eco-justice to protecting the rights of refugees, social media-driven organizations like GetUp!, Jhatkaa, and Compact are reaching thousands of supporters and proving influential. For example, GetUp! sparked public debate in Australia when the government sought to deport 267 asylum-seeking families. Through multiple Facebook events in cities like Melbourne, Newcastle, and Perth, thousands were mobilized, and the Australian refugees were released back into the community.

"Reflect on what’s important to you and prioritize it daily, unapologetically."

Disability design podcast Contra* recently aired an episode on the topic of hashtag activism. Black disability activists and scholars Dr. Moya Bailey and Vilissa Thompson, LMSW (@VilissaThompson and @RampYourVoice) discussed how hashtags can be a vital way of locating and building solidarity within communities experiencing multilayered oppression. For many disabled folks, they might be the only one in their town with a disability. That experience makes it difficult to identify as disabled because popular media tells us to overcome disability.

Focus shifts then to an individual feeling as though they are a pariah, and the only way they can achieve acceptance is to disidentify with their disability. Hashtags like #CripTheVote created by Alice Wong (@SFdirewolf) and #ThingsDisabledPeopleKnow created by Imani Barbarin (@Imani_Barbarin) challenge popular narratives and mobilize community through civic participation and daily truisms. In the process, these hashtags create space for an otherwise diffuse community to come together and celebrate a diverse but group identity.

Thank you so much for your time and thoughts here, Josh. Do you have any parting words for us–particularly for any emerging designers who may read this?

Reflect on what’s important to you and prioritize it daily, unapologetically. Don’t seek stasis; seek confusion (pandemonium even). How else will you know that you're growing? In the midst of that growth, however, make time to enjoy the best of life: Spontaneously telling someone you love them, doodling for fun, drifting through your city stoplight by stoplight. Laugh. Cry. Fill and be filled. Contrary to popular belief, emergence need not be a spectacle. You might be the only one who knows you’ve emerged. And when you do, drift some more.