Hot Topic: Zika Virus and Virology

While the world's eye is laser-focused on the Summer Olympics in Rio, amid all of the feats of strength and showcases of athleticism lies a dangerous disease: Zika. The Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization (PAHO/WHO) reports 166,000 suspected and confirmed cases in Brazil for the period January 2016 to July 2016.

While WHO states that the threat of Zika spreading rampantly during the Olympics is actually quite low—possibly because of seasonal change as it is now winter in Rio when mosquitoes are less active and the Brazilian population has started to develop immunity—the mosquito-borne or sexually transmitted pathogen is rearing its ugly head in the U.S.—specifically, in Florida. In the U.S. and its territories alone, 7,373 laboratory-confirmed Zika cases have been reported for the period January 1, 2015–Aug. 3, 2016. The U.S. is just one of the 65 countries and territories with active Zika virus transmission.

In response, the National Institutes of Health's National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) launched a clinical trial of a vaccine intended to prevent Zika virus infection. The early stage study will look at the vaccine's ability to generate a protective immune response in 80 healthy participants. The Phase I clinical trial, dubbed VRC 319, introduces the vaccine, which is a "small, circular piece of DNA—called a plasmid—that scientists engineered to contain genes that code for proteins of the Zika virus," according to NIAID. "When the vaccine is injected into the arm muscle, cells read the genes and make Zika virus proteins, which self-assemble into virus-like particles. The body mounts an immune response to these particles, including neutralizing antibodies and T cells. DNA vaccines do not contain infectious material—so they cannot cause a vaccinated individual to become infected with Zika—and have been shown to be safe in previous clinical trials for other diseases." This investigational approach is similar to that used by NIAID for West Nile virus.

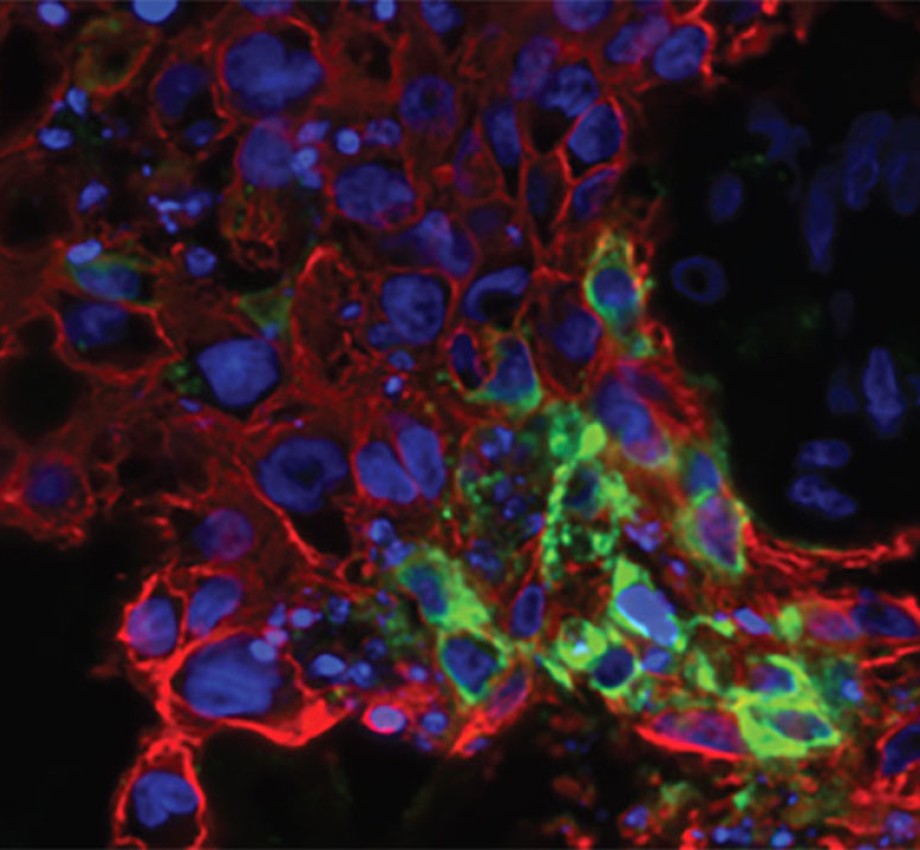

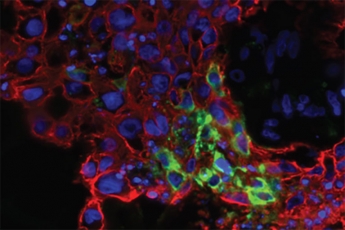

Other researchers are focused on finding ways to stop transmission of the virus from infected mothers to their developing fetus, including collaborators from the UC Berkeley School of Public Health and UC San Francisco. Using a placental model system, the research team of Drs. Eva Harris and Lenore Pereira found that an antibiotic called duramycin, produced naturally by bacteria, can block infection of human placental tissue. The image above is from this research, showing cytotrophoblasts, a type of cell in the chorionic villi. They are stained green with antibodies to a nonstructural Zika virus protein, indicating active replication of the virus. The red stain identifies the cells as cytotrophoblasts, while the blue highlights the cell nucleus. Photo courtesy Takako Tabata/UC San Francisco.

While progress is being made in the laboratory to developing a vaccine to curb the spread of Zika, attention is also focused on how to stop it at the source: the Zika-carrying mosquitoes. Additional work by public health professionals, clinicians, epidemiologist and researchers is necessary to educate, devise new strategies and develop new tools to reduce and prevent the threat of current and future vector-borne diseases. The WHO Vector Control Advisory Board recently convened and reviewed five existing and potential vector control tools to reduce the prevalence of infectious mosquitoes or the exposure to mosquitoes, including:

- targeted residual insecticide spraying

- microbial control of human pathogens in adult vectors (symbiotic Wolbachia spp. bacteria)

- mosquito population reduction through genetic manipulation (transgenic mosquitoes--OX513A, and CRISPR/Cas9 technologies).

This is where you fit in. As Zika virus continues to spread throughout the Western Hemisphere and around the globe, trained professionals in the fields of infectious disease research, medicine, clinical laboratory science, epidemiology and public health will be essential members of the multidisciplinary team needed to combat this and other globally emerging viruses.

In UC Berkeley Extension's Virology course offered this fall, students will receive training in Zika virus molecular biology and transmission, and will review and discuss the latest topics in clinical and laboratory research on Zika virus and other emerging and re-emerging viruses impacting our world today. Students may also be interested in taking courses to obtain an in-depth study of immunology, molecular biology, medical microbiology and epidemiology. Additionally, for students wanting to learn about the aspect of conducting and managing clinical research trials, we offer courses and a professional certificate in this area, as well.