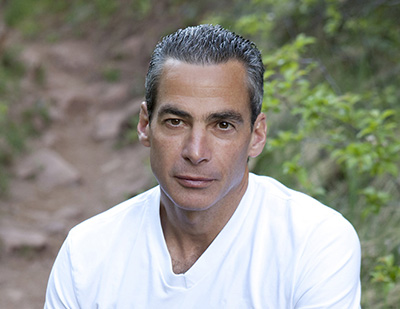

“Write what you know.” Every time I speak to one of our writing graduates, this is the first piece of advice I hear for someone to beat the odds and get their work published. Another piece of advice I’ve heard is, “Write from a place of empathy and utilize your imagination.” After reading the reviews of writer and former Extension writing instructor Paul Cohen’s The Glamshack, I wondered from which place he wrote. Cohen’s road to published fiction writer wasn’t straightforward; I recently asked him about the journey.

You've worked in a variety of fields over the years (i.e., journalism, teaching, marketing) and now you've published your first novel. How does being a novelist fit in with your other work?

A few years after I got my journalism degree from Columbia University—and had been published in national magazines—I realized my true love was fiction. So I got another master’s: This time in Fine Arts at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Iowa offered me a teaching scholarship, which put me on the path to teach writing. Later, Studeo (a strategic content marketing platform for real estate) came along, which proved to be a fun and intense way to pay the rent (as well as a rich source of material for my fiction). Now it looks like I’m moving back into teaching writing. So goes the life of a writer. Through all of the different jobs I’ve held, I’ve always been a novelist. Being a writer is not an avocation or even a vocation—it’s an identity. It’s a visceral sense of this is what I’m here for. I had that, and I’ve got it still. It’s something for which I’m grateful.

Learning to be a teacher also taught me how to be a better writer.

According to the synopsis, The Glamshack is an intense love story. In it, your protagonist, Henry Folsom, is so smitten with an engaged woman, with whom he has a months-long affair, that he develops a plan to fight to any end for her love. What inspired you to write such a story?

The idea for The Glamshack came from an old-fashioned source—heartbreak. I wrote the first draft of the book in a pool house in the Silicon Valley woods while I was also teaching at Extension. I remember it was an El Niño year: Rain came unceasingly and coyotes clicked their bunny-stained canines outside at night. Writing (and running) was a salve to a wound, and I wrote as if in a fever.

Fevers break. How long did the entire process take?

Once I had a first draft, I took a step back and really began to craft the novel. Crafting was an arduous process because, while the fevered first draft lent the book electricity, it also produced a creature that seemed to speak in a foreign tongue. My task was to translate, over and over again. Once I had a presentable draft, I asked the late writer James Salter, who had been a teacher of mine at Iowa, for an agent referral. I thought Salter had ignored my plea, but a couple of months later an agent called me from New York to say she’d just finished the manuscript she’d received from Salter, and she was “breathless.” I remember thinking that I’d arrived—visions of cushy visiting writer gigs at prestigious universities danced in my head.

Thankfully (because I wouldn’t have handled it then with grace), fame did not happen. Some editors to whom my agent submitted the book tried to buy it and were shot down by higher-ups. Among those editors was Josh Kendall, who is currently an executive editor at Little Brown. Subsequently, he nominated The Glamshack for Pushcart Press’s Editor’s Book Award—which is “occasionally given to a worthy manuscript that had been rejected by a commercial publisher”—because he wanted to buy the book but couldn’t. So I put the book in a drawer and started writing another. Then Leland Cheuk, who read an early version of the book, started 7.13 Books with the mission of publishing the best—and sometimes the best-overlooked—literary debuts. His editing ideas for The Glamshack were brilliant. Plus he’s a great guy with a lot of integrity, and I was pleased to accept.

For 12 years, you taught a range of our creative writing workshops and courses: Introduction to Writing Fiction and Developing the Novel, among others. From developing those courses and teaching them, what is the most important thing that you have learned from the experience?

I spent many, many hours developing those courses, organizing class-time flow, and reading and marking student work, but the most important thing I learned was how to listen to my students and respond in the moment. The classroom is a kind of current: You can walk in there as the teacher with a detailed plan of action, but if you don’t listen and respond to the current, you’re liable to find yourself underwater. If you do listen and respond, the experience for both teacher and students can be thrilling. At a certain point, I realized that this tricky balancing act of planning and improvising was also a critical part of the act of writing fiction. So I suppose learning to be a teacher also taught me how to be a better writer. And, of course, teaching at Extension introduced me to a rich literary community that is crucial to every writer’s survival.

Your classes are electives in our Post-Baccalaureate Certificate Program in Writing. What advice do you have for students—either in this program or taking single courses—who are looking to write their own breakthrough novel?

Writing is not an avocation or even a vocation—it’s an identity, and a proud one at that. For me, this belief has allowed me to do various jobs while still staying connected to my core purpose—writing, and writing regularly. This belief also has given me the strength to play the long game. Having said that, I know from experience that a writer needs affirmation from the world from time to time. So my advice is: Send out work, make connections in the literary community, reach out to published writers when appropriate and stay the course.